If like me you teach in a post-secondary educational Institution, then the Spring semester for the Academic Year 2021 has just started for you. This means that up to this moment we have spent weeks of preparing materials, days of organizing content, nights of creating assessments, and hours of tech-training to try and make sure that all goes well. Fingers crossed!

Now that the semester actually started, the marathon starts! Remote teaching, meeting with learners on Zoom, assessing, grading, encouraging and supporting learners, and giving them timely feedback while of course continuously working to make sure that it all goes well. Fingers still crossed!

Amidst all these variables, educators often forget about one important variable: themselves. Research conducted in a variety of teaching environments shows that most educators tend to think about themselves last, or even forget about themselves altogether, especially since the COVID-19 crisis started (Bracho, 2020; Geary, 2020; Park et al., 2020). At the same time research shows that educator self-care is one of the most important elements needed for guaranteeing a successful teaching/learning journey for teacher and learner alike (Beltman et al., 2011; Bracho, 2020; Geary, 2020; Park et al., 2020).

What then can we do to maintain self-care? Take a day off? Have an in-home spa day (you know, pandemic and all)? Spend quality time with the family? All of this is great and is much needed, but what about educator self-care while they are working? Do educators have to wait for the “break” to be able to take care of themselves? What does the research say? What advice do experts have for us that would help us be successful educators while still taking care of ourselves? Here are a few recommendations:

- Acknowledging the need for self-care

The first and perhaps the most important thing educators need to do is to acknowledge the fact that they are going to need self-care. This acknowledgment needs to then be followed by tangible and concrete steps to provide and maintain self-care. Gray (2020) describes our lives post quarantine as Groundhog Day-like where: “Days in quarantine became strangely repetitive, with the position of the sun telling us what time of day we were living in” as we try to manage to live the new normal. Hence, she adds: “Pandemic life cast a spotlight on the importance of treasuring the measured happiness of quarantine life, the power of harnessing our voice for good, and the necessity of physical and emotional care” (Gray, 2020).

- Discovering Overexcitability, and channeling it

In her paper about educator self-care, Gray (2020) shares how channeling her Overexcitability helped her in her self-care efforts. Overexcitability (Gray, 2020) she says is “defined as an innate tendency to respond in an identified manner to various forms of stimuli, both external and internal.” This tendency was first identified by Piechowski (Piechowski, 1999). This tendency manifests itself in 5 styles, namely: psychomotor, sensual, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional. Once identified, this tendency can help deal with challenges as it provides the optimal response to an intense stimulus. Gray shares that she has a psychomotor tendency which means that for her, moving helps her respond to the stimuli of an external challenge. Therefore, to help in the process of self-care she preplanned opportunities to be active, such as runs and walks. The need to move became intensely clear to Gray when due to an injury she had limited her ability to channel her psychomotor tendency. This helped her recognize “the important lessons of the necessity of self-care and flexibility” together (Gray, 2020).

At first glance, Overexcitability tendencies do not seem related to work activities. And this may be true. However, intellectual Overexcitability can readily be coupled with work-related activities. Two birds, one stone!

- Emotional awareness

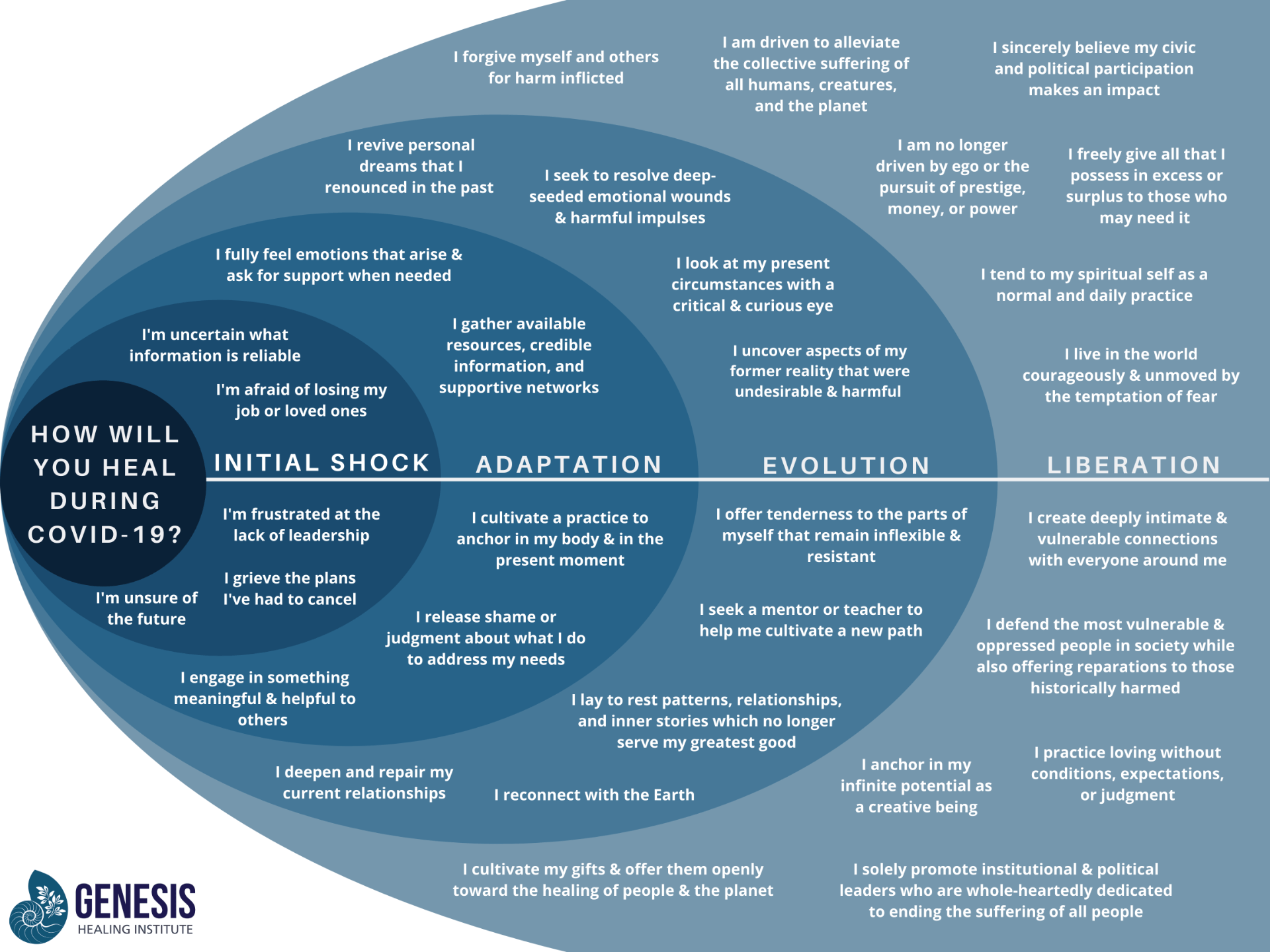

Bracho (2020) encourages educators to consistently incorporate practices that help focus on emotional awareness during these challenging times. She reports that in her classes she began incorporating breathing exercises and personal check-ins at the beginning of each of her synchronous class sessions. For the breathing exercises, she used the website Calm to take one minute to breathe deeply and center the class, before going forth with the lesson as planned. As to the personal check-ins, Bracho (2020) talks about using the chart developed by the Genesis Healing Institute on “Healing During Covid-19” (Ren & Puente, 2020) as well as an adaptation of the Feeling Wheel; a tool that was designed explicitly for expanding awareness of emotions (Wilcox, 1982). These practices, she stresses, helped both her students as well as herself to look after their emotional being, connect with their inner selves as well as with one another in –and this is the key point, a non-judgmental way.

- Social Support in the Workplace

Social support can be defined as “an individual’s perception or experience of affection, care, value, belonging, or assistance in connection with others or networks of others” (Masheder et. al., 2020). Taylor (2011) tells us that “research consistently demonstrates that social support reduces psychological distress.” It also contributes to physical health and survival (Taylor, 2011).

When talking about social support in the workplace, we are specifically identifying the network group to be colleagues and associates who either work in the same institute or organization. They could also be individuals who perform the same type of work at other institutes and organizations. Park et al. (2020) found that social support in the workplace enhances educators’ resilience. “Teacher resilience is a relatively recent area of investigation which provides a way of understanding what enables teachers to persist in the face of challenges” (Beltman et al., 2011). Enhanced resilience due to receiving support in the workplace helps educators “carry out adequate self-care, which leads them to personal wellbeing, as well as more effective professional functioning” (Park et al., 2020).

- Continual Pedagogical Improvement

Lesh (2020, p.369) includes “Continual Pedagogical Improvement” in her suggestions for educator self-care. She stresses the extreme importance for educators to continue learning new techniques and strategies that would help improve their professional skills by reading, pursuing professional development opportunities, conducting action research, and attending conferences. She views these efforts as leading to educators’ delight as they proceed in performing the work that they cherish the most (Lesh, 2020).

In addition to that absolutely essential quality time with the family and loved ones, the above recommendations can help you survive and thrive in the workplace. A final recommendation is to take your time, try them all and discover which one works for you best. Recommendation #5 is one that resonates strongly with me. I do find comfort in reading recent research because it never fails to provide me with sound guidance that helps me overcome various pedagogical challenges. Writing about what I read is yet another source of comfort. I can confidently say that taking the time to discover the self-care strategy that works best for you is absolutely worth the time and effort you invest in it.

References and Resources:

Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., & Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: A review of research on teacher resilience. Educational research review, 6(3), 185-207.

Bracho, C. A. (2020). Reclaiming Uplift: Caring for Teacher Candidates During the Covid-19 Crisis. Issues in Teacher Education, 29(1/2), 12-22.

Geary, C. (2020). Lessons from Pandemic Teacher Candidate Supervision. Issues in Teacher Education, 29(1/2), 104-112.

Lesh, J. J. (2020). Don’t forget about yourself: Words of wisdom on special education teacher self-care. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 52(6), 367-369.

Masheder, J., Fjorback, L., & Parsons, C. E. (2020). “I am getting something out of this, so I am going to stick with it”: supporting participants’ home practice in Mindfulness-Based Programmes. BMC psychology, 8(1), 1-14.

Park, N. S., Song, S. M., & Kim, J. E. (2020). The Mediating Effect of Childcare Teachers’ Resilience on the Relationship between Social Support in the Workplace and Their Self-Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8513.

Piechowski, M. (1999). Overexcitabilities. In M. Runco & S. Pritzer (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (vol. 2, pp. 325-334). Waltham, MA: Academic Press.

Ren, N. & Puente, N. (2020, April). How will you heal during COVID-19? Genesis Healing Institute. https://genesishealinginstitute.org/cv19-response

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review.

Wilcox, G. (1982). The feeling wheel: A tool for expanding awareness of emotions and increasing spontaneity and intimacy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12(4), 274-276.